SHARE

INFO

- DATE: 30-08-2020

- PLACE: Germany

COUNTRY OF PROVENANCE

Germany

RELATED ARTICLES

Hygge or happiness in Denmark

During our on-the-road trip in Denmark I found a beautiful word: hygge, a sense of warmth, intimacy, a door to happiness.

Always in quarantine, Andrea and Giuliana: in health and sickness

Andrea and Giuliana have been living in quarantine for a while, a Parkinson’s has put them in front of a new life, keeping their promise “in health and sickness”.

Journey into words … Responsibility

Journey into words … Responsibility. We often associate the word with a sense of heaviness, but what is it and how can it affect us and others?

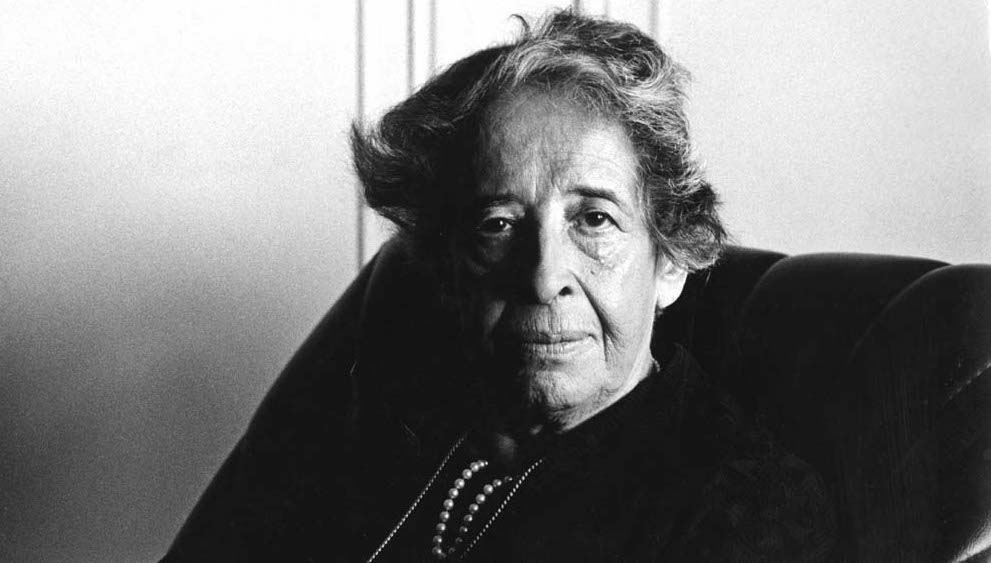

Passing through Hanover… Hannah Arendt

During my last trip around Europe I listened to philosophy podcasts (those of Tlon on Audible) and I happened to pass near Hanover, Germany, the birthplace of a great woman, Hannah Arendt. Since it has been a strange journey, I cannot tell about a person I have met for real, because I have met a few, so these lines go to her, a great personality of the twentieth century who has influenced many other thinkers with her thoughts up to today.

Arendt was born in 1906 in Hanover and will have to leave Germany at some point because she is Jewish. She will travel first to France and then to the United States, where she later settled. She was a charismatic woman, as a young woman she loved to dress in colorful and extravagant clothes and, wherever she was, she was able to create a community around her. In the 1920s, when she was at university, she met Martin Heidegger, another much loved philosopher but also much criticized for his initial Nazi infatuation, and they fell in love despite him being already married and her professor.

Hannah Arendt has never defined herself as a philosopher, rather a political theorist, the values of life as a relationship with the other, especially in the public space, of pluralism, action, responsibility and the importance of human beings precisely as such have oriented her work and her thinking. Her “amor mundi” is a powerful idea, as is her vision of power and civil disobedience to overcome self-interest and build new communities. Arendt still has a lot to say, but we’ll see it later, I’ll try to reflect on this in the next few lines.

The love between Arendt and Heidegger

Hannah Arendt met Martin Heidegger in 1924 and a very strong, all-encompassing love was born between them. She was 18, he was already an established Professor who attracted students from all over the country. In 1925 Heidegger wrote to Arendt “the devil has taken me”, the contact with her was strong and mind blowing. It was he who broke up their relationship and wrote her the reasons in a letter in which he decides to give up on her, he needs to go into his depths and wants isolation, so he retires to the Black Forest: “I prefer to stay away from you than to be close to you but to be far away ”, he writes to her. Everything he observes is finished, everything is transient, we die, but at the same time there is something that never ends, which allows entities to exist (Ref. Being and Time).

Heidegger needs to be alone to carry out his research, while for Arendt everything is relationship, sharing, action is important. And just as she thinks of dedicating her greatest work to him, “Vita Activa”, he adheres to Nazi ideas, perhaps in the name of an obsession with purity for which, according to him, the Jew was describing a way of being in the world that had to be dismantled , a metaphysics that devalued the rest of thought.

Although he will later distance himself from Nazism because it does not fully embody his ideas – Heidegger tries hard to invent new words, to write what he feels and what he thinks, but something always escapes him, there are things that cannot be said – the rift with Arendt is now too deep, she is already elsewhere.

Philosophical inspiration

Hannah Arendt will be very inspired by Heidegger, especially with regard to the idea of a human being as “dejection” in the sense that he is thrown into the world in an impersonal way and is hidden from himself, while gradually taking on a dimension of himself through anguish. This reveals the sense of nullity of being in the world. But while for him man does not live in time but is being there, his “ex-istence” itself a temporalization delimited by death, for Arendt life is the crucial term and action in public space the true meaning of existence.

It’s easy to forget about humanity and religion when you think of characters like Eichmann. She asks the New Yorker to assist as a correspondent for the newspaper at the trial and publishes a series of articles that will converge in what is perhaps her best known work, the “Banality of Evil”. The crimes of the Holocaust are not only against the Jews, they are against humanity and she – as a human – wants to understand how a person can forget that he is human and perform inhuman acts. For this she has been heavily criticized, how can she separate from being Jewish herself?

The Banality of Evil

Arendt has a great capacity for abstraction, she goes to the heart of the matter. When I read Primo Levi’s “If This Is a Man” at school, I was terribly ill as what he says is that the task of Nazism was not just to judge Jews by forgetting that they were human, but by making themselves, in the concentration camps, forget they were.

Eichmann did not break orders, he was a good bureaucrat, he did a job in the mortuary chain. He did not feel guilty, rather a victim because he was just a trivial piece of that mechanism, but if you look at humanity, you are attacking the very beginning of life. Going into everyday life: how often in our life do we limit ourselves to saying yes or no because that’s what they told us to do?

In “The origins of totalitarianism” Arendt wonders how Nazism and fascism managed to take root. She explains the transition that has taken place from previous narration to communication typical of mass society.

The return to the Greek roots

In conceiving mass society, Arendt takes up some ideas of her first husband, Günther Anders, who reflects on technology. In “Man is antiquated”, Anders says that technology cannot exist without thought, otherwise it alienates us. This is not only true in the technique taken to the extreme in the extermination camps, but even today when we blindly believe in science or entrust our lives and intimacy to social media, often without thinking about what this means in terms of tracking and selling our data.

Arendt also takes up some of Marx’s ideas, especially that of the alienation of the individual in mass society that led us to move away from a time of life to find ourselves stuck in some gears. Arendt does not share the concept of work as the value of the human being that Marx, Locke or Smith give. She goes back to the roots of ancient Greeks: action in society, in public space, is important for the human being, and perhaps we have forgotten it.

Before the state did not deal with the economy, but today yes, we are interested in what the state does for us in terms of money, for the economic benefit we can derive from it. We are educated to take not to give, while the concept of Greek Aretè means “I try to excel to give something to others”. In Vita Activa, Arendt says that it is important “not to fall on each other”, to separate the private, intimate space from the public one.

Not to fall on each other

To bring these concepts into today’s reality, an act of normalization takes place in social media – in the same logic of totalitarianisms that prevented diversity – because there are normalizing groups and niches. The more we are in that group or the more we do certain researches (eg the earth is flat), the more we will tend to find groups, opinions, data that confirm our beliefs, there is no possibility of comparison (ref. Eco Chamber Concept) .

Niche, race, ethnicity, are all generalizations that tend to eliminate otherness, they are the first moves of totalitarianism. Arendt puts back at the center the idea of community that has been lost with mass society, but she does not indicate a perfect type of community, she only says that it should be pluralistic, open. Initially, Nazism and Fascism were welcomed by the population, not imposed. The Islamic Revolution of ‘79 in Iran was also welcomed by the population. We must pay attention.

The problem with Eichmann is not so much his monstrosity as the fact that he doesn’t feel responsible. How do you do an inhumane action and then go home and kiss your children?

Ask yourself: and after, what?

“Normal” people like Eichmann did what they did because they didn’t ask themselves: How will I live after doing these actions? Did they adhere uncritically to a dogma? But you ask yourself these questions even if you adhere to a dogma, perhaps they could not imagine an idea of community, a polis in which the relationship with the other cannot be too conflicting, cannot be taken for granted, but it passes through education for living together.

The only thing that saves us, for Arendt, is Amor Mundi, which means offering oneself freely to the other. It is not enough to be intelligent, you need to have imagination! We need to come up with ideas, learn not to be indifferent, know how to make differences, not adhere unconditionally to something.

Ideas belong to nobody, they come into the world. The “birth is a healthy carrier of the unexpected“, it creates a new shift in life, a possibility. When we are empty of ideas and slaves of chatter we are in danger! You can learn to have memory by empathically feeling the condition in which people lived in a certain time, what the idea of being human was at that time, avoid saying “it was better when it was worse”.

Social networks

Social networks are our public space, there are people destroyed by the pillory of shit storms. We are always willing to destroy a person based on something he or she has done, perhaps even only one thing for which too easy conclusions are drawn about the whole person. For that single act, maybe a bad performance, that person loses their job, is removed from the family, and so on.

Ours is a society that constantly binds to judgment not in the sense of Kantian or Arendtian criticism, but on the basis of rankings. We pay attention to what others think because we are afraid. Imagining being a community at the time of social networks, in a time in which the culture from the writing from goes digital, means not losing attention, learning to ask questions, not living alone in anguish: do we respect the dignity of the other and him / her of ours when we write a post? Or “are we falling on each other”?

Power is not an abstract thing, power is all of us – Foucault would say – and each of us in our actions embodies an idea of the world, an image of community. We can decide in our daily life which idea of the world to embody; pluralistic, inclusive, or the opposite. This is a choice that can only be made by those who ask questions.

Disobedience

When the masses give themselves a desire, an appetite, totalitarianisms are born. The people who manage to ride these appetites by manipulating them are the dictators. Those who act politically (ie for the good of the polis) act in a democratic way, for the good of all, especially minorities. Those who develop a standardized vision have personal interests, not political ones!

Voting is only the basis of democracy; politics should be the ability to express one’s own Areté. What do we excellently do that we give to others? Arendt speaks of civil disobedience and starting from the texts of the American Thoreau. The bottom line is I want to live in a society that has rules that I like, otherwise I break them so I can change them. It is very difficult for us Europeans to disobey, in the United States this concept seems more anchored, just look at the recent “black lives matter” movement.

Equality (gender, race, ethnicity, migrants…) needs the activity of both sides! Civil disobedience is precisely the overcoming of self-interest and only those who truly love the laws can do it. These are the premises that allow us to live well together even if we believe in different things. Ethics in public space is to take care, to coexist without falling into each other. Let’s do it! Let’s pay attention.